Skilled Teachers: A Critical Part of Bridging the Digital Divide

A few years ago, a discussion of the digital divide centered first around devices and then about access. Schools with few devices worked to find ways to add to their computer labs, and today many districts are moving to class sets of devices for each classroom, mobile computer/ipad carts, expanded computer labs, or a 1 to 1 device per student implementation. As districts purchase more

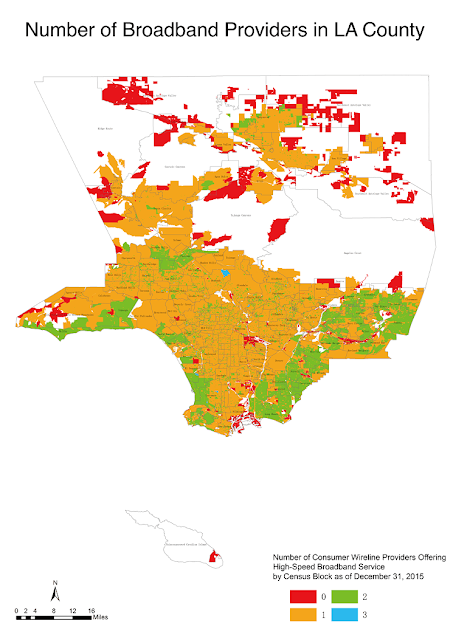

technology, many realize that their wifi infrastructure is inadequate and cannot handle the increase traffic from school and student devices. When the infrastructure is inadequate to begin with, districts scramble to figure out how to increase bandwidth as well as security. Great strides are being made in this area, but much work remains to be done -- especially in some financially strapped rural and inner city districts. In general, an emerging definition of digital equity involves access to devices, access to broadband, and access to consistent opportunities to sharpen skills within in the classroom.

What is fast becoming a critical part of the digital divide//digital equity equation, though, is teacher training. There are certainly superb examples of technology use in most schools where teachers and students are using devices to transform classrooms into a dynamic and collaborative learning environment. However, these examples are often the result of a skilled teacher who is willing to experiment and innovate with technology. This means going beyond assigning online worksheets or drill and kill tasks and providing technology uses that engage and foster higher level thinking and collaboration.

The great challenge, though, is teaching educators how to use technology in transformative ways and to do this in a systemic manner. This doesn't mean that all teachers need to teach in the same way. Efforts to mandate uniformity seldom succeed. However, there should not be vast differences in tech use within the same grade level at the same school, or within the same grade levels at schools in the same district.

Districts throughout the U.S. have found out that implementing technology without adequate training leads to both wasted money and wasted opportunities. When new chromebooks or ipads gather dust in a back of a classroom because a teacher isn't sure how to use them effectively, everyone loses. Devoting money and personnel for professional development and tech mentoring in a systemic manner is critical. In the end, technology can magnify both good teaching and bad teaching. Figuring out how to support all teachers (and not just applaud the few great examples of tech use within a district) is critical in providing a quality and engaging education for all students. A district can have access to devices and adequate connectivity, but without a district wide focus on training teachers in best practice, digital divides will continue to appear.

Districts throughout the U.S. have found out that implementing technology without adequate training leads to both wasted money and wasted opportunities. When new chromebooks or ipads gather dust in a back of a classroom because a teacher isn't sure how to use them effectively, everyone loses. Devoting money and personnel for professional development and tech mentoring in a systemic manner is critical. In the end, technology can magnify both good teaching and bad teaching. Figuring out how to support all teachers (and not just applaud the few great examples of tech use within a district) is critical in providing a quality and engaging education for all students. A district can have access to devices and adequate connectivity, but without a district wide focus on training teachers in best practice, digital divides will continue to appear.

Districts throughout the U.S. have found out that implementing technology without adequate training leads to both wasted money and wasted opportunities. When new chromebooks or ipads gather dust in a back of a classroom because a teacher isn't sure how to use them effectively, everyone loses. Devoting money and personnel for professional development and tech mentoring in a systemic manner is critical. In the end, technology can magnify both good teaching and bad teaching. Figuring out how to support all teachers (and not just applaud the few great examples of tech use within a district) is critical in providing a quality and engaging education for all students. A district can have access to devices and adequate connectivity, but without a district wide focus on training teachers in best practice, digital divides will continue to appear.

Districts throughout the U.S. have found out that implementing technology without adequate training leads to both wasted money and wasted opportunities. When new chromebooks or ipads gather dust in a back of a classroom because a teacher isn't sure how to use them effectively, everyone loses. Devoting money and personnel for professional development and tech mentoring in a systemic manner is critical. In the end, technology can magnify both good teaching and bad teaching. Figuring out how to support all teachers (and not just applaud the few great examples of tech use within a district) is critical in providing a quality and engaging education for all students. A district can have access to devices and adequate connectivity, but without a district wide focus on training teachers in best practice, digital divides will continue to appear.